Botnets have existed for at least a decade. As early as 2000, hackers were breaking into computers over the Internet and controlling them en masse from centralized systems. Among other things, the hackers used the combined computing power of these botnets to launch distributed denial-of-service attacks, which flood websites with traffic to take them down.

But now the problem is getting worse, thanks to a flood of cheap webcams, digital video recorders, and other gadgets in the “Internet of things.” Because these devices typically have little or no security, hackers can take them over with little effort. And that makes it easier than ever to build huge botnets that take down much more than one site at a time.

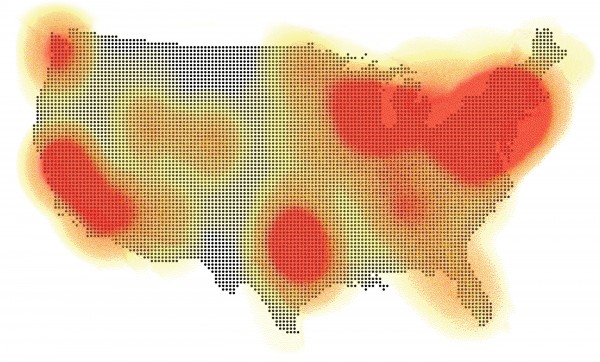

In October, a botnet made up of 100,000 compromised gadgets knocked an Internet infrastructure provider partially offline. Taking down that provider, Dyn, resulted in a cascade of effects that ultimately caused a long list of high-profile websites, including Twitter and Netflix, to temporarily disappear from the Internet. More attacks are sure to follow: the botnet that attacked Dyn was created with publicly available malware called Mirai that largely automates the process of coöpting computers.

The best defense would be for everything online to run only secure software, so botnets couldn’t be created in the first place. This isn’t going to happen anytime soon. Internet of things devices are not designedwith security in mind and often have no way of being patched. The things that have become part of Mirai botnets, for example, will be vulnerable until their owners throw them away. Botnets will get larger and more powerful simply because the number of vulnerable devices will go up by orders of magnitude over the next few years.

What do hackers do with them? Many things.

Botnets of Things

- BreakthroughMalware that takes control of webcams, video recorders, and other consumer devices to cause widespread Internet outages.

- Why It MattersBotnets based on this software are disrupting larger and larger swaths of the Internet—and getting harder to stop.

- Key Players- Whoever created the Mirai botnet software

- Anyone who runs a poorly secured device online—including you? - AvailabilityNow

Botnets are used to commit click fraud. Click fraud is a scheme to fool advertisers into thinking that people are clicking on, or viewing, their ads. There are lots of ways to commit click fraud, but the easiest is probably for the attacker to embed a Google ad in a Web page he owns. Google ads pay a site owner according to the number of people who click on them. The attacker instructs all the computers on his botnet to repeatedly visit the Web page and click on the ad. Dot, dot, dot, PROFIT! If the botnet makers figure out more effective ways to siphon revenue from big companies online, we could see the whole advertising model of the Internet crumble.

Similarly, botnets can be used to evade spam filters, which work partly by knowing which computers are sending millions of e-mails. They can speed up password guessing to break into online accounts, mine bitcoins, and do anything else that requires a large network of computers. This is why botnets are big businesses. Criminal organizations rent time on them.

But the botnet activities that most often make headlines are denial-of-service attacks. Dyn seems to have been the victim of some angry hackers, but more financially motivated groups use these attacks as a form of extortion. Political groups use them to silence websites they don’t like. Such attacks will certainly be a tactic in any future cyberwar.

But overall, the trends favor the attacker. Expect more attacks like the one against Dyn in the coming year.Once you know a botnet exists, you can attack its command-and-control system. When botnets were rare, this tactic was effective. As they get more common, this piecemeal defense will become less so. You can also secure yourself against the effects of botnets. For example, several companies sell defenses against denial-of-service attacks. Their effectiveness varies, depending on the severity of the attack and the type of service.

Bruce Schneier, chief technology officer at IBM Resilient, is the author of 13 books on cryptography and data security.

No comments:

Post a Comment